In an historic vote that will have widespread implications for the United Kingdom, the European Union, and the world for years to come, voters in Great Britain voted yesterday to leave the European Union, prompting Prime Minister David Cameron and one of his top lieutenants to announce their resignations in the wake of the defeat and setting into motion forces that could tear Europe, and perhaps even the U.K. itself apart:

LONDON — Britain has voted to leave the European Union, a historic decision sure to reshape the nation’s place in the world, rattle the Continent and rock political establishments throughout the West.

Not long after the vote tally was completed, Prime Minister David Cameron, who led the campaign to remain in the bloc, appeared in front of 10 Downing Street to announce that he planned to step down by October, saying the country deserved a leader committed to carrying out the will of the people.

The stunning turn of events was accompanied by a plunge in the financial markets, with the value of the British pound and stock prices in Asia plummeting.

The margin of victory startled even proponents of a British exit. The “Leave” campaign won by 52 percent to 48 percent. More than 17.4 million people voted in the referendum on Thursday to sever ties with the European Union, and about 16.1 million to remain in the bloc.

“I will do everything I can as prime minister to steady the ship over the coming weeks and months,” Mr. Cameron said. “But I do not think it would be right for me to try to be the captain that steers our country to its next destination.”

Despite opinion polls before the referendum that showed either side in a position to win, the outcome nonetheless stunned much of Britain, Europe and the trans-Atlantic alliance, highlighting the power of anti-elite, populist and nationalist sentiment at a time of economic and cultural dislocation.

“Dare to dream that the dawn is breaking on an independent United Kingdom,”Nigel Farage, the leader of the U.K. Independence Party, one of the primary forces behind the push for a referendum on leaving the European Union, told cheering supporters just after 4 a.m.

Chuka Umunna, a Labour lawmaker, called the vote “a seismic moment for our country.” Keith Vaz, another Labour legislator, said: “This is a crushing decision; this is a terrible day for Britain and a terrible day for Europe. In 1,000 years, I would never have believed that the British people would vote for this.”

In Berlin, the German foreign minister, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, called the news “truly sobering” and said, “It looks like a sad day for Europe and for Britain.”

Britain will become the first country to leave the 28-member bloc, which has been increasingly weighed down by its failures to deal fully with a succession of crises, from the financial collapse of 2008 to a resurgent Russia and the huge influx of migrants last year.

It was a remarkable victory for the country’s anti-Europe forces, which not long ago were considered to have little chance of prevailing.

Financial markets, which had been anticipating that Britain would vote to stay in, started plunging before the vote tally was complete, putting pressure on central banks and regulators to take steps to guard against a spread of the damage. Economists had predicted that a vote to leave the bloc could do substantial damage to the British economy.

Mr. Cameron had vowed before the vote to move quickly to begin the divorce process if Britain opted to leave. But he suggested on Friday that he would seek to calm the atmosphere before taking any action. In the meantime, nothing will change immediately on either side of the Channel, with existing trade and immigration rules remaining in place. The withdrawal process is expected to be complex and contentious, though under the bloc’s governing treaty it is effectively limited to two years.

For the European Union, the result is a disaster, raising questions about the direction, cohesion and future of a bloc built on liberal values and shared sovereignty that represents, with NATO, a vital component of Europe’s postwar structure

For the European Union, the result is a disaster, raising questions about the direction, cohesion and future of a bloc built on liberal values and shared sovereignty that represents, with NATO, a vital component of Europe’s postwar structure.

Britain is the second-largest economy after Germany in the European Union, a nuclear power with a seat on the United Nations Security Council, an advocate of free-market economics and a close ally of the United States.

The loss of Britain is an enormous blow to the credibility of a bloc already under pressure from slow growth, high unemployment, the migrant crisis, Greece’s debt woes and the conflict in Ukraine.

“The main impact will be massive disorder in the E.U. system for the next two years,” said Thierry de Montbrial, founder and executive chairman of the French Institute of International Relations. “There will be huge political transition costs, on how to solve the British exit, and the risk of a domino effect or bank run from other countries that think of leaving.”

Europe will have to “reorganize itself in a system of different degrees of association,” said Karl Kaiser, a Harvard professor and former director of the German Council on Foreign Relations. “Europe does have an interest in keeping Britain in the single market, if possible, and in an ad hoc security relationship.”

As I noted heading into the vote yesterday, the polling on Brexit had been so close in the final weeks of the campaign that it was hard to tell which side had the momentum. Two weeks ago, it looked as though the pendulum had swung decisively in favor of ‘Leave,’ for example, but then the murder of Labour MP Jo Cox, which was motivated at least in part by the same kind of nationalism driving the Brexit campaign, seemed to turn the tide in favor of ‘Remain,’ which had had a slight edge for months before public attention really started to pay attention to the race. In the end, though, the popular support for the arguments of the ‘Leave’, propelled by forces that had been in place for decades now proved to be too powerful.

As The Guardian’s Rowena Mason notes in her excellent write up of the forces that brought Great Britain and Europe to this momentous crossroads, Europeskepticism has been a part of British politics from the moment that the United Kingdom joined the common market in the early 1970s and only increased as the years went on. What started out as largely a movement among backbenchers eventually became a nationwide political movement that gained voice not only in entities such as Nigel Farage and UKIP but also a large swath of the Conservative Party and even some segments of the Labour Party. In part this was motivated by economic conditions and the belief that the U.K. was getting the raw end of a deal that was benefiting bankers and international financiers on one end, and the “sick” nations of Europe on the other, such as Greece, which better off European nations were constantly being asked to bail out. Added on top of that was the issue of immigration, which has become an especially hot topic in recent years due to the refugee crisis from war-torn parts of the Middle East and Northern Africa and the threats of terrorism that this has brought to Europe itself. Combined together, all of this apparently proved to be all too powerful for the more sober, less emotional arguments for remaining in the E.U. to rebut.

It will be years before the full implications of the Brexit and its economic consequences are known, but already one can see the beginnings in both the United Kingdom and Europe itself. Given that it comes just over a year after a masterful political triumph in the 2015 General Election, David Cameron’s decision to resign as head of the Conservative Party is perhaps the biggest initial political earthquake, but it’s hardly surprising. Cameron went all in on supporting the ‘Remain’ forces, as did most of the leadership of both major parties, and the fact that it lost is a decisive blow against him. Additionally, as Cameron noted in his remarks today, whomever is Prime Minister will be primarily responsible for negotiating the terms of Great Britain’s withdrawal from the E.U. and it would arguably be problematic to have that process headed by someone who had campaigned against the very idea of leaving the E.U. Cameron’s resignation sets up a battle for leadership of the Conservative Party, of course, and it’s widely expected that former London Mayor and current MP Boris Johnson, who was effectively the leader of the ‘Leave’ campaign, will throw his hat in the ring. Whether he has enough support in the party to pull off a win is an open question, though, as is the question of whether a post-Brexit Tory government would last until the next scheduled General Election in 2020. It’s also unclear how these results will impact the future of the Labour Party, which was also split between ‘Remain’ and ‘Leave’ as well as British politics in general, which were noticeably divided on this profound issue.

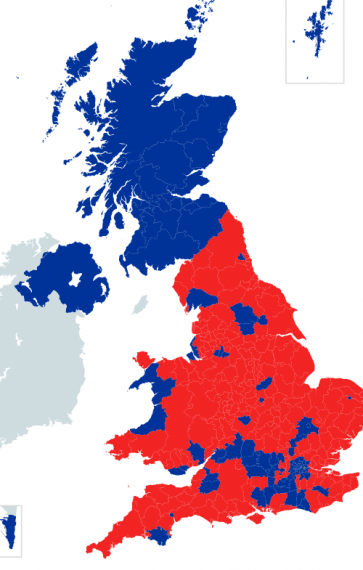

The bigger implications for the United Kingdom from this vote, though, are the question of just how united it will remain in the wake of the vote to leave the European Union. The best way to start that discussion is by looking at this map from The Telegraph, which shows how ‘Leave’ and ‘Remain’ fared around the United Kingdom, with blue representing areas where ‘Remain’ received the majority of the vote and red representing the areas where ‘Leave’ won:

Majority support for leaving the European Union was, as this map shows, essentially nearly entirely an English phenomenon, although some pockets in that country, such as the area around London and other parts of the country that rely on international finance and international trade voting overwhelmingly for ‘Remain.” In Scotland and Northern Ireland, the story was completely different, with the majority of people in both regions voting to remain in the European Union, all of which is leading to speculation that the largely English decision to leave the E.U. could lead to the break-up of the United Kingdom itself. Already today, Nicola Sturgeon, the First Minister of Scotland and head of the Scottish National Party has said that her party will push for another Scottish Independence Referendum in the wake of the outcome of the Brexit vote. Given the popularity of the E.U. in Scotland and the promise of the SNP that it would immediately apply for EU membership if voters approve independence, it’s easy to see how the outcome of a second referendum could be quite different from the first. Across the Irish Sea in Northern Ireland, the Deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland reacted to the outcome of the Brexit vote by suggesting it was time to consider a referendum on the unification of all of Ireland. The only part of the United Kingdom that seems as though it will stay loyal is Wales, where voters largely supported leaving the European Union along with their English neighbors. It will likely take time, but it seems clear that the United Kingdom is likely to emerge from Brexit far less united than it is today.

Finally, the most lasting implication of the Brexit vote may be the extent to which it energizes anti-Europe forces in other nations. There are already signs that this is precisely what is happening, with leaders of nationalist parties in nation’s such as France and The Netherlands calling for similar referendums in their countries. It will likely be some time before that happens, but the fact that a nation like the United Kingdom is now going to start the process of leaving Europe suggests strongly that the entire E.U. experiment is about to be questioned in a way that it has not been until now. Whether the idea of a united Europe survives at all is entirely uncertain.